SwRI Principal Engineer Dr. Graham Conway is sparking debate with his views on electric vehicles. Conway presented his ideas in a TEDx San Antonio talk, which now has thousands of views on YouTube. In this episode, he explains why he believes describing electric cars as “zero emissions” doesn’t tell the whole story. He urges listeners to examine where the electricity that powers battery-operated vehicles comes from. If the power source creates pollution, can the technology truly be considered zero emissions? Conway provides valuable insight for the environmentally aware driver.

Listen now as we hear a new perspective on electric vehicles.

Transcript

Below is a transcript of the episode, modified for clarity.

Lisa Peña (LP): If you're looking for a cleaner way to drive, you'll want to hear from our guest today. He's an engineer comparing the environmental impact of gas-powered, electric, and hybrid vehicles, his surprising findings next on this episode of Technology Today.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

We live with technology, science, engineering, and the results of innovative research every day. Now let's understand it better. You're listening to the Technology Today podcast presented by Southwest Research Institute.

Hello, and welcome to Technology Today. I'm Lisa Peña. We're not back in our studio yet, so we are recording today through web conferencing. Our guest today is SwRI Principal Engineer Dr. Graham Conway. Dr. Conway works closely with the Environmental Protection Agency and automotive industry suppliers and manufacturers. He conducts engine testing and modeling and tracks changes in industry regulations. He's talking to us today about his intriguing findings on the environmental impact of zero-emissions electric vehicles. Thank you for joining us today, Graham.

Image

SwRI Principal Engineer Dr. Graham Conway shared his controversial perspectives on electric vehicles in a TEDx San Antonio talk, which now has thousands of views on YouTube. Graham says electric vehicles cannot be considered “zero-emissions” unless the electricity that powers them comes from a zero-emissions source.

Graham Conway (GC): Hi, Lisa. It's good to be here.

LP: Hi. So I was intrigued by your TEDx talk. So you presented a TEDx San Antonio talk. It was really eye-opening. So to start, will you recap your talk for our listeners?

GC: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, so the TEDx talk was last November time. And it was a discussion about electric vehicles and maybe some of the misconceptions about electric vehicles, mainly that they have a badge, as you said yourself, of being zero emissions. And that kind of puts an emphasis or puts a focus on an aspect of them that I think needs to be challenged.

And that's basically what the talk was about. It was looking at, how do we measure emissions from our cars and transportation? What types of emissions are we looking at? How do they impact the planet that we live on? And really, how can we as a consumer and we as a bigger part of a society make the right decisions that will be the best for our planet in the end?

And really, the big takeaways are that maybe things like hybrids would be something that should be considered by a lot of people today for their next car. And that as a people and as a society, we should be looking at improving the internal combustion engine at the same time we're looking at making battery electric vehicles more available to people.

LP: So what I found interesting and what really brought it home for me was you had this diagram. And I'll try to explain it to our listeners, but it showed how we need to expand our vision of emissions. So inside the circle, maybe the zero-emissions car is not putting out - well, it's putting out zero emissions. But if you took a wider approach and looked at the big picture, your information was that it actually is not as environmentally friendly and it's not - zero emissions may not be accurate. Can you touch on that a little bit?

GC: Yeah, absolutely. So I guess to go back a little bit, it would be the way we currently measure emissions in the automotive industry, especially for the cars that you and I would drive, is we hook up a emissions measurement device to the exhaust. And then we drive it over a prescribed distance at a certain speed, and then we measure the emissions that come out of that. And then that's what we use to say what the fuel economy numbers are and what the emissions are from that vehicle.

Now, if you try and do that measurement technique on a battery electric vehicle, you're going to come up with an answer of zero because there is no tailpipe making those emissions. And that's where the moniker of zero emissions comes in, and everybody's fairly comfortable with that because, as I said, that is the true result when you try to measure it like that. But my point is that there is a lot more to it than just what's coming out of the tailpipe of the vehicle. And that's where we come to the box you were talking about where I had an image of a vehicle sitting in the middle of the screen.

Image

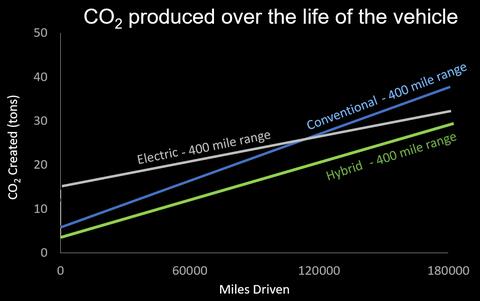

Conway collected data showing that building and powering an electric vehicle generates more CO2 than a hybrid or conventional gas-powered vehicle up to 120,000 miles. You would have to drive the electric vehicle more than 120,000 miles over its service life for emissions to fall below that of a gas vehicle. Conway believes a hybrid vehicle is the cleanest driving option.

It was an electric vehicle. And again, if you just put the measurement box around the vehicle, you don't get anything like CO2, and you don't get anything like NOx emissions. But that vehicle doesn't power itself by magic. It uses electricity.

And that means, well, you really have to look at where the electricity comes from and how the electricity is generated. And if you do that, you draw a box around a much bigger picture. And then you start to see that in certain places our energy isn't quite that clean. So we burn coal in power stations to make electricity, and that puts out a lot of emissions.

So if you put that same emissions measurement device in the power station, you'd find a lot of emissions. But because we don't currently measure things like that, electric vehicles are zero. And everything else is just grouped in a term called bad. So that's really something that I hope a lot of people would get out of that talk if they watched it is just to consider that the emissions are coming from more than one source.

LP: So when you compare the emissions of electric vehicles in the big picture, meaning the emissions generated by generating that electric power to power an electric car, and you compare that to a gas-powered vehicle, how do the two compare emissions-wise? I mean, we know that there are emissions coming out of the gas-powered car itself. But if you compare the two, what do we get?

GC: Yeah, so if you - again, gasoline or diesel - for the U.S. market, it's mainly gasoline that we put into our cars. It's a really obvious answer, or it's a really obvious number where that's coming from. For the electric vehicle, it's a lot more difficult for just a singular electric vehicle to know what the number is because it's not localized. It's not a localized measurement. There's lots and lots of different things happening along the journey that they sort of tie into that number.

I would say that if you just look at the CO2, and CO2 is really the thing that we're talking about when we're trying to compare these two. You would look at the CO2 being produced on the electric vehicle, and it is much lower than the internal combustion engine vehicle. The electric motor is far more efficient than an internal combustion engine. And a lot of the ways we generate the electricity are more efficient than something that's required to refine the fuel.

So if you look at the electric vehicle, it is much lower than the battery electric vehicle. But it really heavily depends on the size of the battery pack in the vehicle. You can have some smaller vehicles, smaller electric vehicles, say the Chevy Bolt or the Nissan LEAF®, which have reasonably small battery packs. And you can compare that to a vehicle that has a larger battery pack. And that's really where the key talking point is. Because a battery pack takes a lot of energy to produce.

And when we talk about energy, we're mainly talking about electricity. And so we need to consider how much electricity is required to make the battery pack that goes into the electric vehicle. Because these vehicles don't magically appear in the showroom where there's a gasoline vehicle or an electric vehicle. They don't just all of a sudden appear in the showroom. Somebody has to make them. Somebody has to mine the raw materials. Somebody then has to fabricate them into a vehicle and deliver the vehicle to the showroom.

And there's energy at each of those steps. And so we need to understand how much pollution is produced at each of those steps. And that's really where things start to become more complicated just because of the huge amount of energy required to make a battery pack, especially a larger one.

And so typically, an electric vehicle will come to the showroom with a bigger CO2 footprint than a gasoline vehicle. And then it's a question of, well, how quickly can it offset that initial CO2 penalty because it is a more efficient vehicle.

And it gets really interesting when you look at different use cases of the size of the vehicle versus the size of an electric vehicle versus how many miles of driving do you do versus which climates do you drive in. It becomes a really interesting and quite complex discussion point. So I guess that was a really long answer to what was quite a simple question of how do they compare, but it's definitely a very complicated situation to look at.

LP: So after seeing your talk, the hybrid kind of emerges as the hero or a good choice in all of this. What makes it a good choice?

GC: Yeah, so for me, I think a hybrid is a good choice based on a number of factors. I think the important ones to consider are that the hybrid is a really fantastic synergy of technologies. So you've got the internal combustion engine, and you've got the electric motor.

And as I said before, the electric motor is really, really efficient compared to an internal combustion engine. And the internal combustion engines we drive are very, very inefficient when we're just driving really slowly. So it doesn't make much sense because you use more fuel when you drive harder. But for the work you're getting out of the engine, you're actually much more efficient when you're driving it along the highway versus in the city.

And so there's a really nice synergy between those two technologies because the hybrid system can take over around town at very low speeds where the engine is very, very inefficient versus the hybrid, which you can drive a hybrid-- if you tried to drive your hybrid vehicle along the highway, you'd run out of battery really, really quickly. And so again, that's just another nice reason that the two work together.

Why they become the hero of my story is because the battery pack in a hybrid is very, very small, generally. Especially the type of hybrids I'm talking about are certainly much smaller than a full battery electric vehicle. And so it has a much smaller CO2 penalty when it comes to the showroom. And therefore, it needs much less time to offset that penalty. But it still gets a lot of the benefits of being more efficient because it has an electric motor on it.

And really, that's kind of what it comes down to, is that I think today, the hybrid is a really, really good choice for most people. But something that wasn't very easy to get across in the 13 or 14 minutes or so in the talk, was just how it really depends on you as a person, the type of driving you do, the type of situation you're in. But I think for a lot of people, a hybrid is a great choice.

LP: So what do you want people to understand about transportation's impact on the environment?

GC: Yeah, so I think transportation itself, it's given a lot of, I guess, column inches in the media, in terms of the negative impact on the environment. There's two real impacts on the environment from transportation. There's the greenhouse gas emissions. So those are responsible for climate change, or we believe they are responsible for climate change.

And that's mainly CO2, so carbon dioxide coming out the back of the tailpipe. That only accounts for about 14% of our total. So from transportation, it's about 14% contribution to our annual CO2 emissions. But I think if you were to just go on what you read and perceptions, you'd think most of the CO2 comes from transportation. But really, it's only quite a small amount.

And then I think the other thing that that's quite critical is the other type of emissions, which we call criteria pollutant emissions. And those are really responsible for bad air quality-- so smog at the extreme level, and then just particulates and small particles, and just generally bad things in the air that you don't want to breathe in in large quantities. And electric vehicles do a fantastic job at cleaning up the criteria pollutant emissions in densely populated places. So in city centers, for example, if you move to electric vehicles, you get rid of all the things that cause bad air quality, or you get rid of most of them.

And so I think that's something I want to get across, is that I don't want to demonize the electric vehicle. I am very much in favor of the electric vehicle in certain environments, and city centers are one of those. But when we talk about the other problem, which is the greenhouse gas, that's CO2, and CO2 comes from making our electricity, as well as burning our fuel. So I want people to understand that there's a lot going on there, and that really, it's not quite the obvious answer to go straight to the electric vehicle, because it's got this 0 in front of it, which makes it a very obvious answer as to what you should go to, when in reality, there's a lot more going on.

LP: Yeah, it's not just-- it's not what it seems, is what your research has found out. So you've been pretty vocal about your findings. So how would you like this information to change people and their decisions around driving choices?

GC: Yeah, so I think first and foremost, it would be, don't just assume an electric vehicle is automatically the best choice for you. For many people, it is. But you need to ask a lot of questions before you're looking at the type of vehicle you want to buy next. And I guess some of the bigger questions would be, well, how many miles do I drive a day? How many miles do I drive a year?

How do I recharge my electric vehicle if I get an electric vehicle? Do I have solar panels locally in my house that I can use to recharge, or I'm going to plug it into the wall where the mix of electricity is a little bit more unknown?

What climate do I live in? So for most people on this podcast, that's going to be a-- I live in Texas where it's really hot, and I use my air conditioning a lot, which can affect the range of the vehicle. For other people, it might be, well, I live in a very cold climate where I'm going to have to turn the heaters on and my range of my vehicle is going to drop significantly.

And I guess the final question would be, what type of driving do I do? Do I do a lot of city driving? Do I do a lot of long distance, high mileage highway driving? And really, once you ask yourself those questions, you can start to move yourself into, well, should I be looking at electric vehicle, should I be looking at a hybrid vehicle? Or is the best choice for me the internal combustion engine vehicle?

And I guess that's another one of my, I guess, things that I like to push and talk about is, the internal combustion engine only vehicle is still going to be around for quite a while. And we shouldn't give up on it yet. We should still put money, put time, put effort, put resources into improving it, into making it more efficient, because it's going to be around for a while. So I hope that would be the information that I would get across, is just to-- as scientists, as engineers and people like that, we generally have an inquisitive mind anyway, so maybe we ask these questions, but for the broader audiences to ask these type of questions.

LP: And once we take a look at our personal habits, and you kind of put in all those factors, you can kind of decide, if you're concerned about your environmental impact, and you can break it down to, well, what works better for me? So you did make a strong case for the hybrid vehicles. Are they generally more expensive? And do you find that that could be a deterrent for some?

GC: Yeah, so absolutely a hybrid is more expensive than, I guess, a non-hybrid equivalent version. So I think a Toyota Camry is a nice example. It comes with a hybrid and a non-hybrid version. The non-hybrid version is about \$24,000. The hybrid is about \$28,000. So you can see there there's a \$4,000 premium to the hybrids. So that's something that you need to consider when you're looking at a hybrid, is you're going to spend a little bit more money.

But then we get into a discussion of what we call the total cost of ownership, which is, well, OK, I bought a hybrid, and as I've discussed before, it's more efficient. So I'll save money on gas, and therefore-- well, when does that pay itself back? How long or how many miles do I have to drive with the savings to offset that \$4,000 original on-cost.

I think another thing I really, really, really want to get across and push is that electric vehicles are much more expensive still. It's really the battery pack in these vehicles that costs. That is where the cost is. And obviously, as you go to a battery electric vehicle, you have a bigger battery, and therefore the cost goes up. So a very, very cheap electric vehicle is about \$30,000. The Nissan Leaf is about \$30,000, versus the \$28,000 Camry. And that Nissan Leaf will have a range of about 150 miles.

So again, this is where I start to ask the questions of people, well, how many miles do you need this vehicle to do? How often will you drive it? Do you need more than 150 miles? Because you can spend a little bit more money for this electric vehicle, but you're going to compromise on some of the capability and some of the performance, unless you go for a much more expensive electric vehicle.

But that's very difficult to afford for a lot of people, especially in the US, where the median household income is about \$60,000 a year. If you look at being fiscally responsible, that is going to mean you can afford a car of about \$22,000 in value. So you can see, we're much lower than the hybrid and we're significantly lower than the fully electric vehicle. And that's really something that I think I want to get across, as well, is that we need internal combustion engines still, because it's a cheap form of transportation, that generally, the bigger population will be able to afford for many years to come, while we wait for battery prices to come down and we wait for the electric vehicle to become more affordable.

LP: So when did you first realize that maybe you had to question electric vehicles a little bit more, and that perhaps they aren't as clean as many would think?

GC: So I don't think I had a light bulb moment. I don't think there was anything that suddenly jumped out at me as, oh, my goodness, that doesn't seem right. I think once I started to see people talking about banning the internal combustion engines. Many, well, states now, and different countries, especially in Europe, are talking about complete bans on the internal combustion engine.

That was the time to become vocal about it. That was the time to start getting different messages across, versus just a, let's just go with the 0 emission vehicle. Because seeing the 0 emissions, that brings about a lot of questions, I think, immediately. Especially for technically-minded people, 0 holds quite a special place as a number and as a concept.

And it's quite binary, as well. Something is 0 or it isn't 0. There's no middle ground. If you're near 0, you're not 0. And so seeing the 0, it impacts me. It makes me angry that people are using 0 incorrectly and inappropriately. And that's kind of where it became my personal mission to try to educate and try to spread different messages.

LP: Yeah, that there's absolutely more to this story, and a lot of people don't realize it. So the general public, who's not involved with this type of research day in and day out, we see that 0 emissions and we take it at face value. But you've brought up a completely different area of how that may not be true. So, great information. So how did you gather the data that's backing up your message?

GC: So there's a lot of it available online. And of course, you can basically say anything you like or write anything you like and put it online. You have to be very careful about what you're actually using to back up what you're saying.

So a lot of it comes from technical papers that I can find online or from conferences that I've gone to where I've seen studies that have been done. It's quite a fascinating topic, in that it's been around forever, as something that's actually going on. But it's only the last, let's say, five years to 10 years, maybe, that it's really gained some sort of traction and become important to discuss and to understand.

LP: OK, so you have collected this data through, as you mentioned, research papers available on the internet and from different sources. But it's your goal to expand this research then, and really bring it to life and get your hands in it. Tell us a little bit more about your plans for expanding it.

GC: Yeah, so I think it needs to be expanded. I think we need to look at it further. And I would definitely like the Institute to be a major player in lifecycle analysis moving forward. I've been trying internally to arrange a symposium or a conference. It's very difficult to do at the moment because of the current situation we're all in. Nobody knows when they're going to be able to travel.

But the idea of that would be to get people with an internal combustion engine background into a room with people who have a battery electric vehicle background and focus, and try to have a discussion, a technical discussion, a philosophical discussion, about what assumptions should we be making when we're doing this type of lifecycle analysis study, that both sets or both sides of the fence agree with. Because you can get somebody who does a study of lifecycle analysis who has just an engine background. You're going to get a very different answer to somebody who does that study with a battery background now.

It's just inherent biases that we have when we're picking our assumptions. And so that's really the aim, is to come up with a set of assumptions, come up with a set of standards that can be used globally, so that when we do this study wherever in the world, we use the set of assumptions that we've come up with in the symposium. And then hopefully, then we can all be singing from the same page as an industry.

LP: Why is it so important for you to get this information out there?

GC: So I guess I strongly believe the internal combustion engine will be required for many decades to come. So elephant in the room for some listeners who maybe are skeptical would be, well, you know, Graham, you're an internal combustion engine guy. Of course you're going to come up with a story that promotes the internal combustion engine. And yes, that is where a lot of my motivation comes from.

But as I've said before, I absolutely believe the future of transportation is the electric vehicle, 100% believe that one day we should all be driving electric vehicles. I just don't think that's as soon as many people say it will be. And therefore, as we've said before, if you politically say something is a 0 emission vehicle, and you should therefore ban any other technology that isn't an electric vehicle, you kind of push the argument or you push the technology path down one route.

And that route specifically will be fund investment in the internal combustion engine, which I think is going to be a problem in 10 or 15 years' time, where we realize, well, we still need internal combustion engines. But now we've missed out on 10 to 15 years of research and development, because we decided, well, we were going to ban them without really having a plan of how we're going to move to 100% electric vehicles.

LP: So I imagine there are some maybe electric vehicle manufacturers who have gotten wind of your message and maybe don't like it. Have you received any pushback for this message?

GC: Oh, loads.

LP: [LAUGHS]

GC: I've had lots and lots of push. But my mentor for my talk-- so when you do a TEDx Talk, you're assigned a mentor, somebody who's given a talk before. And mine was excellent. I couldn't have asked for a better mentor, a guy called Ali who works at Central Catholic High School downtown. And he said, look, Graham, if people don't push back against you, then it wasn't a message worthy of a TEDx Talk in the first place. It should be controversial. It should be challenging. It should be thought-provoking.

I've had a lot of people who are supportive of the talk. And generally, it's people involved in the oil and gas industry and the internal combustion engine people. They're like, this is the message that needs to be getting out there. And then there's people on the electric side of the fence, who will disagree with specific parts of the talk, which I'm absolutely OK with. As I said, it's data that's been gathered and it's data that could be questioned. And I love having those discussions.

But I find it very-- I seldom find people disagreeing with my overarching message of, we should be doing a better job of quantifying the emissions from the lifecycle. And one of my messages is, I absolutely believe the future of transportation is the electric vehicle. So that's saves me in a lot of arguments, in that I'm not just seen as a guy who just wants the internal combustion engine to succeed. So I think, yes, I've have a lot of pushback, but generally, it's on specific small parts of it where people have other data that suggest a slightly different message. But the overall conclusion and the overall message, I generally had very positive feedback on.

LP: All right, but you are up for the challenge if someone's wanting to challenge your message, so I like that.

GC: Absolutely.

LP: Yeah, absolutely. OK, so what are you driving? If not too personal of a question, what do you drive and why?

GC: So I currently drive a 5 Series BMW. And in my household, we also have a truck. So we have those. Those are our two, I guess, main vehicles. It might surprise people to know I used to own an electric vehicle, up until a couple of years ago. I was on a lease for about three years. It was a BMW i3 electric vehicle. So as I say, I'm not against electric vehicles. I don't have a problem with the technology or what the vehicles are.

One of the main motivations for me for getting that vehicle at the time was the cost. It was super cheap to get it, just because, I guess we're in Texas, and five years ago nobody really wanted an electric vehicle. And there were lots of government incentive programs that made the cost really, really good. So it was really interesting as a jump into the competitive space and get a first-hand experience of it. And I guess, as I say, I've got two internal combustion engine vehicles. But I try to ride my bicycle a lot, sometimes to work, sometimes just for doing small errands, to, I guess, try to offset my carbon footprint a little bit.

LP: Do you have any plans to get a hybrid at some point?

GC: Yeah, I think, absolutely, my next car I will strongly, strongly consider a hybrid.

LP: What do you enjoy about this line of work?

GC: So I really enjoy working with the clients. I learn a lot from talking with our clients. And something I really like to do is learn. If I don't learn something, at least one little fact or one little piece of information, that's been a bad day. I just love asking questions and getting answers. And there's very few places I would imagine better to be than the Institute for that type of environment, in terms of just, one, asking questions. That's very well-received in this working environment.

And two, you've oftentimes got people around the Institute who can actually answer your questions, which is quite unique. You don't have to spend six hours getting lost in Google searches to understand something. You can just pick up the phone and call somebody who's been working on it for 45 years. And they can give you the answer.

And then I guess the other thing I really enjoy about work is the travel, going to see different parts of the world, and understanding the-- I go to Japan a lot, because there's a lot of-- an automotive base in Japan, with Honda and Toyota and Nissan and with people like that. And understanding their requirements, it's a very different set of requirements and a very different set of challenges to, for example Europe or the US. And that's again, going into working with clients and understanding their problems and trying to solve them. Unfortunately at the moment, that all has to be done online. But hopefully one day, we'll be back to normal.

LP: That's what we're all hoping for, just like our recording of this podcast. We're normally in our studio, but here we are today on a webcast. And I think we've learned so much from you today, no matter the method of hearing your voice. But really, you've enlightened us and given us a wider perspective on this issue.

And I really did enjoy your TEDx Talk. And we will post the link to that on our episode page so our listeners can check that out. So thank you for all this great information today, Graham, really interesting insight on how vehicle choice can impact the environment. I enjoyed having you.

GC: I really enjoyed being on. Thanks a lot, Lisa.

Our segments Breakthroughs and Ask Us Anything are on hold for now. Before we go, we have some good news to share. We can now say we are an award-winning podcast. Thank you to the San Antonio Chapter of the Public Relations Society of America for recognizing the Technology Today Podcast with a 2020 El Bronce Excellence award. The podcast team is grateful for the honor.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

And that wraps up this episode of Technology Today. Subscribe to the Technology Today Podcast to hear in-depth conversations with the people changing our world and beyond through science, engineering, research and technology.

Connect with Southwest Research Institute on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube. Check out the Technology Today Magazine at technologytoday.swri.org. And now is a great time to become an SwRI problem solver. Visit our career page at swri.jobs.

Ian McKinney and Bryan Ortiz are the podcast audio engineers and editors. I am producer and host, Lisa Peña.

Stay safe and thanks for listening.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

The fourth High-Efficiency Dilute Gasoline Engine (HEDGE-IV) program incorporates new and more aggressive efficiency, performance, and emissions goals that are in line with existing and potential future regulations and expectations. The overall goal is to develop the most cost-effective solutions possible for future gasoline engine applications.

How to Listen

Listen on Apple Podcasts, or via the SoundCloud media player above.