Multi-Robot Manipulation of Heavy/Bulky Objects

The manipulation of heavy and bulky objects is a challenging endeavor in the field of robotics. These tasks often necessitate the use of large robots with high payloads and substantial power requirements. In our latest research, we have tackled this problem by developing a multi-arm, force-feedback system specifically designed for the intricate and high-stakes application of loading munitions for military applications. Our focus has been on creating a more efficient and reliable method to handle these heavy-duty tasks, with a particular emphasis on improving object alignment and insertion precision. In this article, we highlight ARMATRIX, an internal research project to determine the viability of a specific multi-purpose approach to bulky object manipulation through a multi-arm system.

This work implemented multi-robot coordination and planning strategies to achieve manipulation and assembly tasks that cannot be easily performed using a single robotic arm. Visual servoing was added into the control scheme of the front and the back robot, to increase the robustness and repeatability of the alignment process. Additionally, this project added a fixed distance between manipulators and segmentation of the high-DOF system into smaller sub-pieces as new constraints to enable the use of the SwRI developed Tesseract framework for multi-robot trajectory planning.

Successful implementation of this approach resulted in a dual-arm robotic system that demonstrates coordinated free space manipulation and peg-in-hole insertion of a bulky object. This approach is robot agnostic and can be implemented with any combination of robotic manipulators. Additionally, though this approach was demonstrated using a dual-arm configuration, this approach could be expanded to incorporate additional manipulators.

Coordination Strategies

How do we enable two robots to effectively coordinate on a task?

Leveraging multi-robot systems can enable more advanced and agile object manipulation and assembly techniques. However, such solutions are more difficult to initially program and integrate due to the inherent complexity of the multi-robot system. We sought to address these implementation hurdles by developing coordination strategies that utilize standard algorithms to complete and to assess multi-robot assemblies. We implemented and evaluated each of the following coordination strategies:

- Master-Follower: one manipulator is primarily responsible for manipulation of the object while the other manipulator maintains course.

- Holder-Manipulator: one manipulator is primarily responsible for holding the object, acting as a dynamic rig, while the other manipulator maneuvers the part.

- Synchronized Motion: multiple manipulators contribute actively to the manipulation of the object through space.

Coordinated Planning

How do we generate trajectories for a multi-robot system?

Tesseract, a SwRI-developed open source robotic planning software framework, within the ROS-Industrial open source project, provides a flexible and extensible framework for various tasks related to robot motion and manipulation. Current path planners that work with Tesseract (e.g. Trajopt, OMPL, and Descartes) use constraints to generate collision-free paths. However, these current path-planning algorithms are poorly suited for high-degree-of-freedom (DOF) systems and additional planning constraints must be considered within the Tesseract framework to properly plan for a collaborative multi-arm system. As such, a significant portion of this internal effort involved implementing additional tools and constraints to plan trajectories for multiple robots simultaneously. We added constraints centered around multiple robot control, parameterized by the object being manipulated and the task being performed.

Demonstration of Bulky Object Manipulation

Our target demonstration for this research involved the insertion of a cylindrical tube into a cylindrical slot, employing a UR10e robot for the rear manipulation and a UR5 robot for the front. To methodically address this complex task, we divided it into three primary sub-tasks, managed by an application layer, Figure 2, to handle transitions between state and manage task completion progress:

- Free Space Movement Task

- Object Alignment Task

- Object Insertion Task

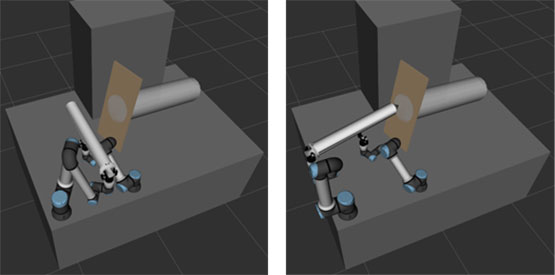

Figure 1. Robot test cell.

The bulky object was preloaded into the system at various starting configurations. In the Free Space Movement Task, the robots coordinate their movements to move the object to a defined goal configuration. During the Object Alignment Task, the front robot positions the tip of the object in line with the insertion slot while the rear robot follows. Finally, during the Object Insertion Task, the front robot maintains alignment with the insertion slot while the rear robot pushes the object into the slot.

Free Space Movement Task

To execute the Free Space Movement Task, we leveraged a combination of SwRI-developed products and industry-standard software packages. We used Tesseract to plan free space trajectories for the 12-DOF (Degrees of Freedom) kinematic chain, where descartes_light generates potential trajectories for each manipulator and a discrete contact check determines which trajectories are valid for the dual arm system. For the execution of these planned trajectories on the hardware, we utilized the ros2_control from the Robot Operating System (ROS), which enabled us to employ the joint trajectory controller effectively.

Figure 2. Application-Level Process Management.

We implemented a synchronized motion coordination strategy, where each manipulator contributes actively to the manipulation of the object through space. For this coordination strategy, the multi-robot system maneuvered the bulky object from a known start position along a preplanned path. Homogenous transformations of the object’s path were used to determine each robot’s path. A joint trajectory controller drove each robot along its preplanned path. Free space movement concluded when the robots completed their trajectories.

Figure 3. Robot system free space starting configuration 1 (left) and end configuration (right).

Object Alignment Task

For object alignment, we implemented a master-follower coordination strategy, where one manipulator is primarily responsible for the manipulation of the object while the other manipulator follows course. For alignment localization, we employed Cartesian motion control as the primary control method for the rear robot (UR10e) and visual servoing as the primary mechanism for the front robot (UR5). This combination ensured accurate and reliable alignment of the object with the slot.

Figure 4. Test rig and April tag used for visual servoing.

Visual servoing is a control technique in robotics that uses visual data from cameras to guide a robot’s movements. It relies on feedback from the robot’s visual sensors to adjust its position and orientation in real time to achieve a desired goal, defined with respect to a visual marker (e.g. an April tag). A Cartesian motion controller commands the forward robot, equipped with an external camera, to align a defined camera frame with a tag frame and ultimately drive the system toward the insertion surface and align the insertion object with the insertion point. During visual servoing, the rear robot is also commanded by a Cartesian motion controller to follow the forward robot.

Object Insertion Task

For the Object Insertion Task, we adopted a holder-manipulator control strategy, where one manipulator is primarily responsible for holding the object, acting as a dynamic rig, while the other manipulator maneuvers the part. The front robot acts as a holder and is responsible for maintaining visual alignment through visual servoing. The rear robot, also using a Cartesian motion controller package, served as the manipulator to push the object into the slot a known distance. This bifurcated yet cooperative setup allowed the front robot to ensure proper alignment while the rear robot executed the insertion, resulting in better insertion outcomes.

Next Steps: Integration of Force/Torque Feedback

Looking forward for the Free Space Movement Task, we anticipate integrating admittance control with the joint trajectory controller. Admittance control is a control strategy used in robotics to regulate the behavior of a robot when interacting with external forces. Here, it will introduce compliance to the forward robot as it moves along its planned trajectory, allowing dynamic coordination between the two robots (e.g. if the rear robot was behind on its trajectory, the forward robot could adjust accordingly). This enhancement aims to mitigate the impact of latency and ensure synchronicity between the dual-arm robotic system during execution, improving the overall performance and reliability.

For the Object Alignment Task, we aim to implement a master-follower with force-control coordination strategy, where one manipulator is primarily responsible for the manipulation of the object while the other manipulator follows course and maintains a zero-force differential. Using zero-force control, the rear robot will react to an external force by adjusting its movement to maintain a zero-force state. In our system, the rear robot will feel the applied forces from the forward robot moving toward the insertion surface and follow along.

Finally, for the Object Insertion Task, rather than requiring a known insertion distance, we aim to use a Cartesian force controller to command the rear robot to exert a force on the insertion object along a vector normal to the insertion surface. Insertion would be completed when the rear robot feels an average force greater than or equal to the applied force in the negative direction of insertion for three seconds. This indicates that the object had been completely inserted into the insertion tube. The duration and force were chosen to elevate the force feedback felt during insertion above the noise floor of the F/T sensor, allowing greater confidence the object had been successfully inserted.

In conclusion, our development of a multi-arm, force-feedback system marks a significant advancement in the field of robotic manipulation of heavy and bulky objects. While there is still work to be done to perfect our system, our results demonstrate a promising step towards more efficient and reliable robotic solutions for complex industrial applications like munitions loading. We are excited about the potential applications of this research and look forward engaging with government and industry to extend this capability for their applications.

For more information, contact David Leake and Matt Robinson.