DETAIL

During WWII, scientific communities in Hanford, Washington; Los Alamos, New Mexico; and Oak Ridge, Tennessee, were tasked with producing the vital components needed to build a nuclear bomb.

During World War II, Manhattan Project scientists raced against Germany to develop the first atomic bomb, sparking the beginning of the nuclear age and creating the weaponry credited with helping end the deadliest conflict in human history.

In 1943, the U.S. established the Hanford Site in Washington, which developed the world’s first production-scale plutonium reactor. Hanford would lead the nation in producing the plutonium needed to construct atomic bombs, which continued through the post-war arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Hanford’s reactors operated until the Cold War ended in 1987.

Over 40 years, Hanford produced 74 tons of plutonium, which also produced roughly 56 million gallons of chemical and radioactive waste byproducts. With shelf lives ranging from decades to thousands of years, this waste poses a risk to human health and environmental safety today and for the foreseeable future.

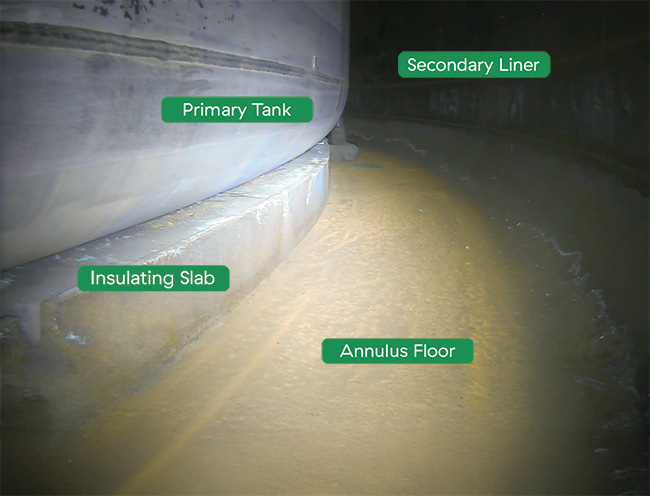

A 30-inch annulus provides limited inspection access to the outside of the primary tank and the inside of the secondary liner. Guided wave technology permits inspection of the tank bottom.

Hanford’s massive double-shell tanks, pictured under construction, each hold up to 1.2 million gallons of hazardous waste.

The original 149 single-shell underground storage tanks had a limited service life, prompting the construction of 28 double-shell tanks (DSTs) that each hold up to 1.2 million gallons of waste. Each DST is composed of a carbon-steel tank inside a carbon-steel liner, which is surrounded by a reinforced concrete shell. The primary tank rests on an 8-inch insulating slab that separates it from the liner and provides both air circulation and leak-detection capabilities. The DST features an annulus, a 30-inch-wide space between the primary tank and the secondary liner that provides limited access to inspect the outside of the tank and the inside of the liner (see double-shell tank graphic). Narrow riser ports further limit access to the tank’s side walls for monitoring and maintenance.

After the Cold War, Hanford shifted from producing radioactive materials to waste management and cleanup, with the Department of Energy (DOE) charged with maintaining the integrity and safety of the aging tanks. The first DST leak occurred in 2012, likely due to a defect and subsequent corrosion in the floor of the primary tank, releasing radioactive waste into the annulus. Inspection technologies available at the time could not detect the defect before a leak occurred.

Conventional inspection methods require direct physical access to the structure to perform integrity measurements, which is impossible due to waste content and structural constraints. Emptying a tank is not feasible, and replacing all 28 DSTs is not physically or economically viable. The best approach to manage these structures is continuous monitoring of tank integrity, and addressing any issues as they occur. Following the 2012 leak, advancing DST inspection technologies became a priority at Hanford.

Challenge Accepted

In 2017, the DOE issued a challenge to the engineering community to develop a solution to improve Hanford tank inspections. With previous experience developing inspection technology to examine steel plates buried in concrete, Southwest Research Institute saw the potential to adapt this inspection principle for the Hanford application. SwRI proposed a nondestructive evaluation (NDE) solution utilizing a guided wave inspection technique, which propagates ultrasonic sound waves over long distances to examine areas normally considered inaccessible.

DETAIL

Electromagnetic acoustic transducers have two basic components: a magnet and an electric coil. The sensor propagates waves directly onto the structure under inspection without a couplant gel, a key advantage for the Hanford application.

Guided waves travel along a structure. When they encounter defects or flaws in the material, resulting echoes can be used to characterize the defect. SwRI has a long history of developing NDE techniques and products using guided waves, including the magnetostrictive sensing (MsS) system that has been commercially available worldwide for over 30 years.

For the Hanford challenge, SwRI modified a sensor previously used to inspect nuclear power plant containment vessels and evaluated its potential for DST inspection on government-owned tank mockups. The development team conducted an internal research and development program to modify the initial sensor system, featuring a large, human-manipulated electromagnetic acoustic transducer (EMAT). After the inspection principle was proven to work, the team turned to the modifications needed to function remotely inside the 30-inch annulus space. SwRI focused on adapting the technology to serve as an all-in-one inspection solution to remotely deploy in, maneuver about, and evaluate the 28 DSTs buried at Hanford.

SwRI adapted this guided wave NDE sensor used to inspect nuclear power plant containment vessels to address the challenges of inspecting underground DSTs at the Hanford site.

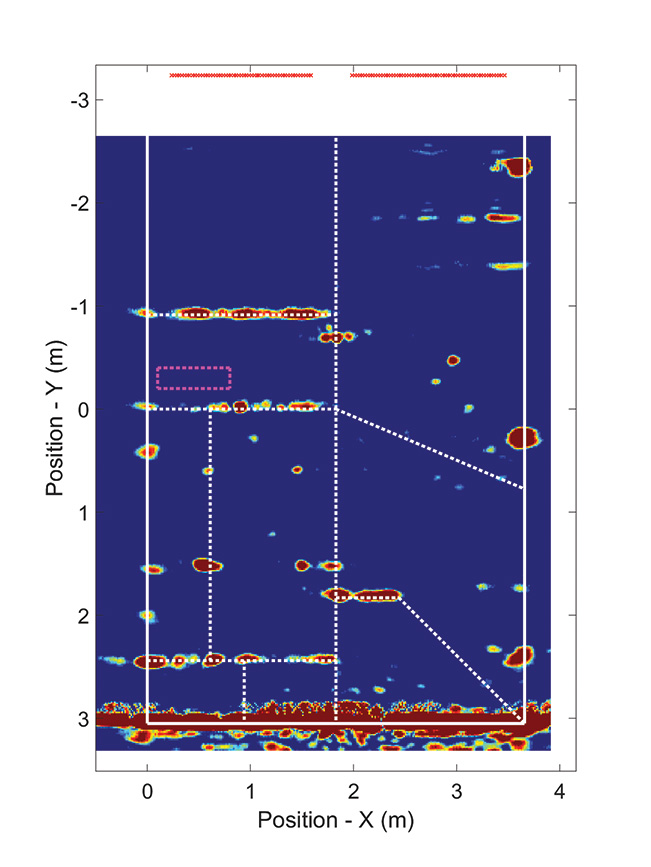

SwRI’s sensor output is processed to create color-mapped images for operator analysis.

The team used the EMAT connected to the side walls of the tank to generate and receive guided waves to inspect the tank’s bottom. The tests demonstrated that SwRI’s sensor could detect flaws like those believed to exist in DSTs and display processed results in color map images. Based on the evaluation’s results, SwRI won the contract to develop a full-scale solution for Hanford.

SwRI developed on-site test setups to demonstrate the ability to deploy a slim-profile robotic inspection system through a 24-inch access riser into the 30-inch annulus.

Miniaturization & Delivery

SwRI aimed to complete two primary tasks when developing its new system. First, the team sought to miniaturize the modified EMAT to fit through the DST’s 24-inch-wide access riser, and second, they needed to design a robotic delivery system to deploy and control the smaller sensor remotely within the DST. To complete their first task, SwRI used advanced electromagnetic and thermal modeling to shrink the original EMAT from 600 pounds to less than 130 pounds, reducing its physical size considerably. The reduced size allowed sensor deployment to fit through the DST’s access riser while maintaining the ability to propagate guided waves at sufficient range to inspect the tank bottom.

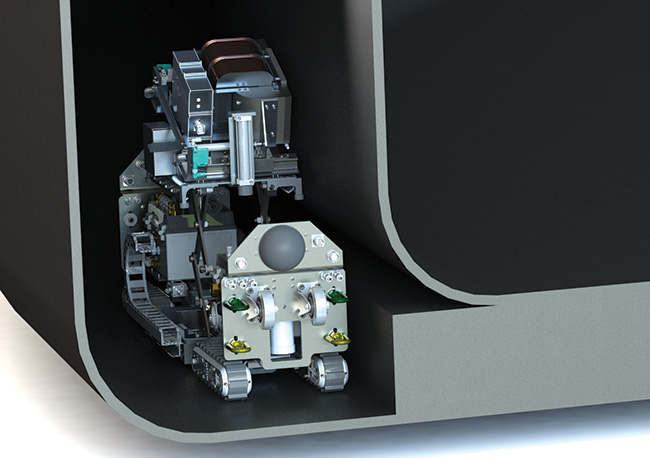

The team then undertook creating and integrating the sensor into a custom-designed robotic delivery vehicle. The system features four robust treads to maneuver within a DST environment and comes with six cameras for operator control and vehicle positioning feedback. At 72 inches in length, less than 21 inches in cross-section, and weighing only 375 pounds, the robotic inspection system can be deployed and retrieved easily through the access risers of all 28 DSTs to conduct inspections.

Once lowered into a DST, the robotic vehicle travels along the tank’s sidewall via the annulus. Operators remain safe at a station hundreds of feet aboveground, controlling operations of the tethered system using custom interfaces to gather the necessary measurements. As the guided waves travel along the walls and bottom of the tank, the EMAT relays the readings back to the operator station. Following tank inspections, the system is retrieved back up through the riser. The system is also “washdown-rated” so any hazardous contaminants from the DST environment can be safely removed before it is handled by operators and redeployed in other tanks.

The miniaturized EMAT sensor is delivered via a robotic vehicle into the DST inspection spaces through the 24-inch-wide access risers.

The sensor, shown integrated into the robot delivery system, weighs less than 130 pounds, considerably lighter and smaller than the original 600-pound EMAT.

Evaluation & Qualification

To date, SwRI’s system has undergone extensive verification testing both at SwRI and at the customer site to demonstrate its capabilities. System testing has yielded thousands of inspection data points, providing a comprehensive understanding of its performance under varying conditions. Using these data, the team has optimized the system’s core parameters. Based on these successful tests, the DOE requested the design and fabrication of a second inspection system that largely mimics SwRI’s original design with a few key changes to improve robustness and operability within the DST environment. SwRI recently completed fabrication of this new system, which is currently undergoing verification testing at the client’s site.

SwRI’s low-profile robotic delivery vehicle with the miniaturized EMAT sensor aboard travels along the DST’s sidewall, maneuvering the sensor into the proper position to propagate the guided waves for tank bottom evaluation.

SwRI staff are demonstrating additional potential uses for the inspection technology, such as evaluating ship hulls or process reactors, where access may be limited or would put operators at risk.

SwRI has also identified the potential for using this same technology to inspect a variety of other large plate-like structures where direct access is either impossible or could put human personnel at risk. Examples include ship hulls, chemical storage tanks, and process reactors. This system could benefit humanity in ways that continue to be revealed. The marriage of novel inspection methodologies with custom robotic solutions promises to remain an active research and development area at the Institute for years to come.

In the meantime, once the second inspection system completes its remaining qualification testing, it will be deployed in Hanford’s 28 DSTs to provide a holistic picture of the state of the tanks and assess any degradation. With millions of gallons of radioactive material held at bay by these tanks, their continued integrity is imperative. SwRI’s technology will become a vital component for determining the DSTs’ remaining life and aid in preventing leak incidents, helping keep thousands of people and the local environment safe.

The multidisciplinary team that developed the robotic inspection systems included Lead Engineer Doug Earnest, Manager Dr. Adam Cobb, Research Engineer Anthony Wagner, Assistant Manager Tori Wahlen, Senior Research Analyst Nikolay Akimov, Group Leader Carlos Barberino and many others.

At only 72 inches in length, less than 21 inches in cross-section, and weighing only 375 pounds, the robotic inspection system can be deployed and retrieved easily through the access risers of all 28 DSTs to conduct inspections.

Questions about the story or Sensor Systems & Nondestructive Evaluation (NDE)? Contact Adam Cobb at +1 210 522 5564 or Victoria Wahlen at +1 210 522 5063.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Adam Cobb is a manager in SwRI’s Mechanical Engineering Division. He is an electrical engineer developing new techniques for nondestructive evaluation and structural health monitoring. His expertise includes ultrasonic testing, radiographic testing and signal processing. Victoria Wahlen is an assistant manager in SwRI’s Intelligent Systems Division, where she leads a diverse team of engineers within the Robotic Platforms Section. She focuses on developing robotics for inspection, confined spaces, textile and warehouse logistics applications.