Batteries, like people, don’t want to be too hot or too cold.

Like the heroine of the classic bedtime story Goldilocks and the Three Bears, batteries prefer their temperatures to be “just right.” The lithium-ion batteries used by nearly every consumer device and electric vehicle on the road tend to degrade or age more quickly when they are outside of this “Goldilocks” temperature range. When it’s too cold or too hot, battery performance suffers.

For instance, during a hot Texas summer, drivers might hear the dreaded “click-click-click” indicating a dead battery. For gasoline-powered cars, this is typically a minor inconvenience, easily resolved with a set of jumper cables or a relatively inexpensive replacement. But with electric vehicles, it can be much more expensive and potentially dangerous to have a damaged battery powering a vehicle. As electric vehicles become more common, it’s important for longevity and safety reasons to find more effective ways to protect batteries from temperature extremes.

Fortunately, Southwest Research Institute is up to the challenge.

EV Thermal Management

In EVs, multiple battery cells are assembled into modules and packs in the smallest possible space, which limits air cooling and amplifies thermal management challenges. Battery temperatures are also affected by environmental conditions, such as ambient and road temperatures and the effects of rain, wind or snow.

A cold battery will use its own energy to generate heat, limiting the power available to the vehicle until it reaches optimal temperatures, and ultimately reducing range. Conversely, in hot weather, the vehicle’s cooling system reduces battery temperatures, consuming more energy and, again, limiting range.

Hot temperatures can also lead to battery failures and thermal runaway propagation (TRP). This is a dangerous, cascading failure in a battery pack where thermal runaway in one cell triggers a chain reaction, causing adjacent cells to overheat and so on. This can cause battery pack failures, fires and even explosions.

Other types of battery failure are often associated with manufacturing defects that lead to internal short-circuits or as the result of abuse, such as car crashes or penetration by a foreign body.

The earliest electric vehicles tried to manage temperatures by using air flowing directly from the cabin to heat and cool the battery. However, they soon determined that this direct connection between the battery and the people in the vehicle was not a good idea, and that technique has been relegated to history.

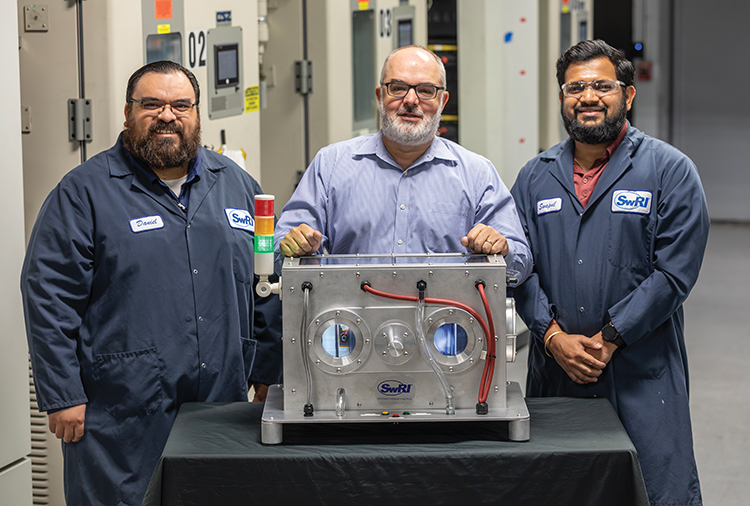

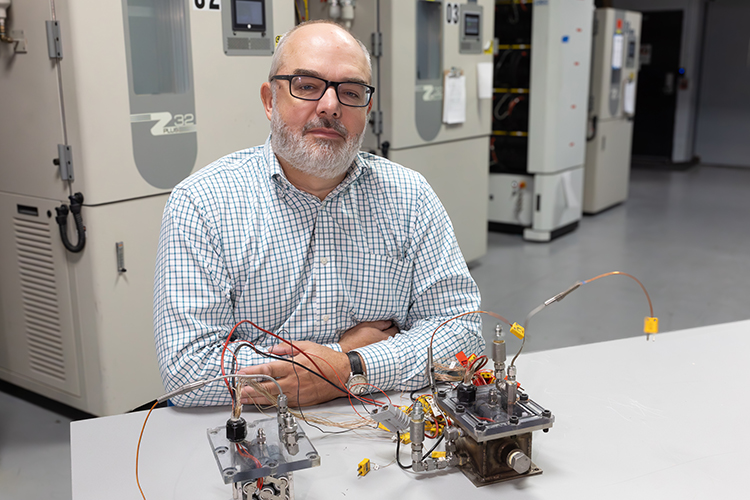

From left, Senior Research Engineer Daniel Robles, Staff Engineer Andre Swarts and Senior Research Engineer Swapnil Salvi

developed an immersion cooling demonstration unit to provide customers with a simulated experience of battery abuse tests.

Liquid Cooling

DETAIL

Ethylene glycol coolant has been used for decades as an antifreeze agent in vehicle and heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems. As a liquid, it is colorless, odorless and combustible. Pure ethylene glycol freezes at −12.8 C (9 F), but, when mixed with water, its freezing temperature drops further, up to a point.

These days, most electric vehicles use indirect liquid cooling to regulate battery temperatures. During this process, a thermal management fluid, or coolant, flows through channels embedded in cooling plates or cooling ribbons that are in contact with the battery cells. The coolant absorbs heat from the battery, transferring it away from the cells. The heated coolant is circulated to a heat exchanger to release the heat and then returned to the cooling ribbon to repeat the process. When the battery is cold, the same fluid is heated externally and uses a reverse process to heat the battery, using either waste heat or an auxiliary electric heater. The fluids used for these applications are typically a mixture of water and ethylene glycol, but pose the risk of hydrogen production through electrolysis should there be accidental contact between the coolant and the high-voltage components.

DETAIL

SwRI manages the Electrified Vehicle and Energy Storage Evaluation-II (EVESE-II) consortium, which is the current evolution of its highly successful EVESE program. Launched in August 2024, EVESE-II expands focus to include module and pack research, with an emphasis on immersion cooling research, test standards, safety testing and applications beyond electric vehicles, such as charging and vehicle-to-everything connected vehicle systems.

As battery power increases, so do the current requirements, or “C-rates,” which are the ratio of the charge/discharge current relative to its maximum capacity. C-rates are particularly significant for direct current fast charging (DCFC) technology. DCFC is the fastest way to charge an electric vehicle, allowing some EVs to reach an 80% charge in as little as 20 minutes. DC fast chargers convert high-power alternating current grid electricity to DC power and deliver it directly to the vehicle’s battery. Fast charging puts additional stress on thermal management technology and may overwhelm indirect liquid cooling, because performance is limited by the thermal conductivity of the cooling pathway. The heat generated from fast charging can degrade the lithium-ion batteries in EVs, so dissipating or managing that heat is vital.

Cold Plunge

SwRI began looking at battery immersion cooling in 2020 during the first Electrified Vehicle and Energy Storage Evaluation (EVESE) consortium, an offshoot of the long-running Energy Storage System Evaluation and Safety (EssEs) consortium. During the four-year consortium, SwRI developed technology to evaluate battery in-service cycling performance and behavior under various conditions.

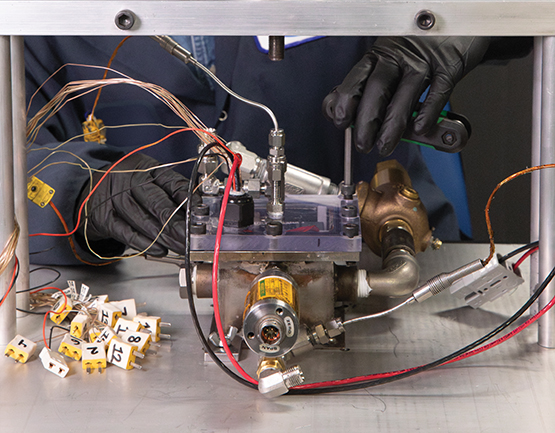

SwRI has developed immersion cooling testing technology, including this mini-module. The tubing delivers coolant to the device during performance testing.

This SwRI-developed mini-module measures the effectiveness of immersion cooling during nail penetration abuse tests.

DETAIL

Dielectric strength is the ability to resist electrical breakdown in the presence of an electrical field. Insulators, for instance, have a high dielectric strength, while conductors have low strength.

Direct liquid immersion cooling involves circulating a coolant between the battery cells to enhance heat transfer by several orders of magnitude. Some studies found 50 to 100 times improvement in the heat transfer coefficient with this method over conventional indirect cooling solutions. Cooling electric systems by immersing them in dielectric fluids began in the late 1800s and is commonly used today to cool electronics and high-end computing technology. Dielectric fluids are designed to prevent or quench electric discharges. Their fluid properties include low electrical conductivity, a high dielectric strength and good heat transfer properties. These dielectric characteristics prevent current leakage that can lead to electrical losses.

Because no specific test methods for evaluating immersion cooling or fluids exist, SwRI developed several test setups that circulate a test fluid around a mini-module comprised of seven cylindrical cells, while continuously charging and discharging the batteries. These tests can run for as long as 20 weeks. During these tests, SwRI monitors the health of the mini-module, tracking any capacity and internal resistance changes. SwRI also evaluates interactions between the fluids, the battery cells and the mini-module’s construction materials by monitoring fluid changes over time. A thorough end-of-test inspection includes destructive physical analysis of the batteries to look for any signs of fluid ingress.

Abuse Research

SwRI Senior Research Engineer Swapnil Salvi fixes a nail onto one of the battery abuse test rigs for a penetration test. The nail will be driven into a battery cell beneath it to simulate potential real-world abuse and effects.

SwRI has developed numerous battery test methods through EVESE and EVESE-II. The SwRI Energy Storage Technology Center®, established in 2018, is one of the few places in the country capable of performing all regulatory safety tests on cells, modules and complete battery packs.

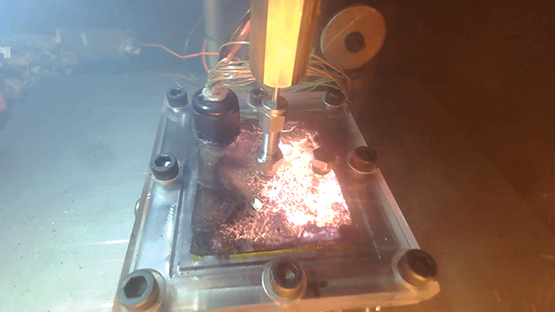

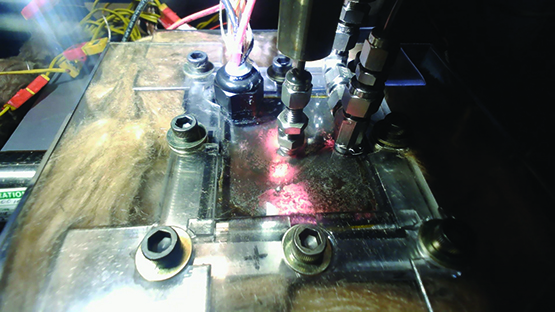

Probably the most dramatic test available is a battery abuse test that involves driving a nail into a mini-module immersion chamber.

As the nail pierces the battery, SwRI also measures temperatures and monitors for evidence of TRP. The lithium-ion batteries in the cell heat up quickly once one is punctured, and the heat spreads rapidly through the rest of the module. SwRI then monitors the emissions produced by the failing batteries and characterizes the dielectric fluid’s mitigating effects. Immersion cooling generally provides improved outcomes, with lower temperatures and better containment, although potential secondary reactions associated with vaporized fluids requires careful monitoring.

SwRI’s cycling and abuse testing is complemented by the development of unique fluid tests aimed at understanding fluid performance, such as heat transfer tests and fluid combustibility tests that produce data beyond what simple lab-scale fluid property tests can provide. SwRI has applied this type of testing to multiple fluid clients to help them understand potential performance benefits and fluid characteristics in battery immersion cooling applications.

Immersion Cooling

Immersion cooling is an attractive technology for many reasons, particularly for ultra-high-power applications, such as motor sports or high-end sports cars. The energy storage system in some Formula 1 cars, for example, comprises a battery pack with direct immersion cooling and a highly specialized dielectric fluid. The powerful engines, high speeds and designs of F1 vehicles require heightened levels of cooling. Today’s standard electric vehicles do not justify the cost and complexity of implementing immersion cooling systems. Tomorrow’s heavy-duty and longer-range vehicles, however, may need it.

Other applications that do not require immersion cooling include battery energy storage systems (BESS), which use repurposed EV batteries to support electrical grids, providing back-up power. These BESS applications do not have weight and volume restrictions and their cell-level power demands are not excessive, so immersion cooling is unnecessary. Even heavy-duty and off-highway applications that use “megawatt” charging solutions are self-correcting with reasonable C-rate levels.

These images demonstrate the benefits of immersion cooling during a penetration test. The left image shows flame spread without immersion cooling three seconds after penetration. The right image shows how immersion cooling is quenching the fire three seconds after penetration.

While battery immersion cooling is not currently used in mainstream vehicle applications, high charging rates, high-power duty cycles and ever-shrinking battery packs for certain off-highway and performance applications may yet leave a niche for battery immersion cooling to fill. SwRI is also investigating immersion cooling benefits and advancement in other applications. The Institute is exploring a related direct cooling application for data centers. These crucial facilities are proliferating to house servers and networking equipment that enable organizations to store, manage and distribute data. They power online activities from web searches to cloud storage and artificial intelligence. Data centers consume significant amounts of energy for information technology and cooling equipment, with consumption expected to increase significantly with the growth of artificial intelligence. Data centers consumed about 4.4% of total U.S. electricity in 2023 and are expected to consume approximately 6.7 to 12% of total U.S. electricity by 2028, and much of that goes toward cooling.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Andre Swarts is the program manager for the Electrified Vehicle and Energy Storage Evaluation-II (EVESE-II) research consortium and a leading member of SwRI’s Battery Systems Research and Innovation efforts. Swarts has more than 30 years of experience in the energy industry.

SwRI is launching a consortium aimed at advancing understanding how immersion cooling and other advanced techniques could address some of the challenges facing data centers and their growing need for power.

SwRI complements testing with a comprehensive battery systems design, analyses and integration service, taking client requirements from concept to validated solution. This includes component, subsystem, system and even final application design, evaluation, prototyping, building and testing. SwRI’s expertise puts it in a strong position to serve those needs, while continuing to provide extensive research and development for the mobility industry.

Questions about the story or Battery Immersion Cooling Testing & Research? Contact Andre Swarts at +1 210 522 6631.