DETAIL

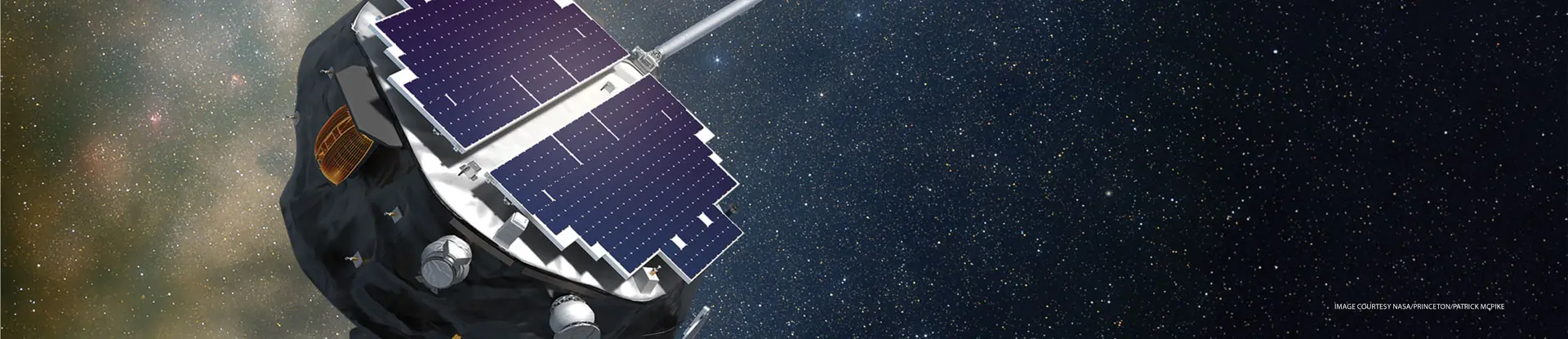

NASA’s Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) was the primary mission payload that launched from Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Sept. 24, 2025. SwRI managed the development and integration of the 10 instruments aboard, including the SwRI-developed Compact Dual Ion Composition Experiment (CoDICE) sensor.

Space is a vast, near-perfect vacuum largely devoid of matter — but it’s not entirely empty. It just contains very few particles compared to Earth’s atmosphere. On average, a dice-sized cube of Earth’s atmosphere contains billions and billions of air particles, but in space, the same-sized cube contains only one or two particles.

This sparse population is mostly hydrogen and helium atoms as well as other gases, in both charged and neutral forms. This medium also contains dust, tiny particles of various elements, including carbon and silicon, scattered throughout.

Of particular interest are high-energy particles called cosmic rays — primarily protons and the nuclei of atoms — traveling through space at nearly the speed of light. Cosmic rays come from various stars including our Sun, as well as from supernovae, colliding galaxies and more. And these high-energy particles are of particular interest because of how they can affect humans and modern life. In the near-Earth environment, exposure to this space radiation can affect astronauts and spacecraft, including the GPS technology that is ubiquitous to navigating life on Earth, including aviation and agriculture. It can also affect electric grid technology.

Image Courtesy of SPACE X

The trio of spacecraft designed to monitor and map the heliosphere and the solar wind that defines it are shown here prior to integration in the rocket fairing at left. SwRI played key roles in both NASA’s IMAP mission, the primary spacecraft on top, and SWFO-L1, the NOAA satellite on the right. The Carruthers Geocorona Observatory on the left is the third ride-share payload.

Exposure to space radiation is regulated by many things, including the Earth’s magnetic field as well as the solar cycle. During solar maximum, the “balloon” around our solar system is fully inflated, offering better protection from galactic cosmic rays. But these active periods produce more powerful and frequent solar activity such as bursts of solar energetic particles associated with coronal mass ejections and solar flares, allowing more of these particles to penetrate the Earth’s magnetic field. For instance, reports from the American Meteorological Society indicated that the powerful solar events in May 2024 wreaked havoc with farmers. Extreme geomagnetic storms disrupted the precise GPS-guided navigation systems used to plant, fertilize and harvest rows of seeds, causing an estimated loss of up to $500 million in earning potential.

Image Courtesy Bae Systems/Benjamin Fry

The sunrise launch of the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket with SwRI-developed instruments and technology aboard symbolized the dawn of a new era in heliophysics and space weather research.

In contrast, at solar minimum, when our Sun is least active, the boundary between the influence of the solar wind and the interstellar medium contracts. This deflated balloon provides less shielding from the background galactic cosmic rays, characterized by very high radiation, from interstellar space.

DETAIL

The enigmatic nature of suprathermal tails stems from their ubiquitous presence across the range of solar wind conditions. These charged particles move at velocities significantly higher than the main populations but do not reach the energies of cosmic rays, even in quiet, undisturbed regions of the solar wind, far from any shocks.

On Sept. 24, 2025, NASA launched two spacecraft loaded with Southwest Research Institute technology designed to better understand and predict these high-energy phenomena. NOAA’s Space Weather Follow-On Lagrange 1 (SWFO-L1) satellite shared a ride to space with the primary payload, NASA’s Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission, along with a third ride-share payload, the Carruthers Geocorona Observatory. The sunrise launch of the SpaceX Falcon 9 payload symbolized the dawn of a new era in heliophysics and space weather research.

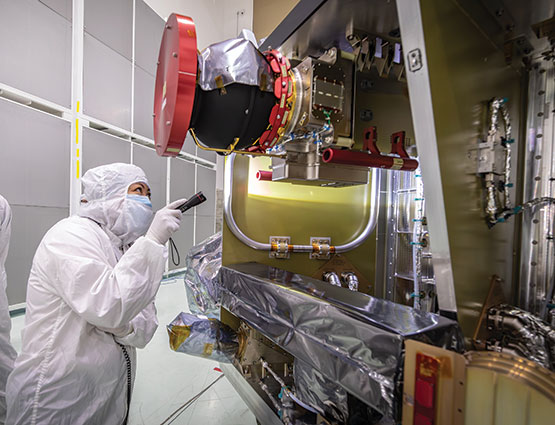

Image Courtesy NASA Johns Hopkins APL/Ed Whitman

Anna Shin, deputy systems assurance manager from the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University, performs a post-integration inspection of the SwRIdeveloped Compact Dual Ion Composition Experiment (CoDICE) instrument aboard NASA’s IMAP observatory.

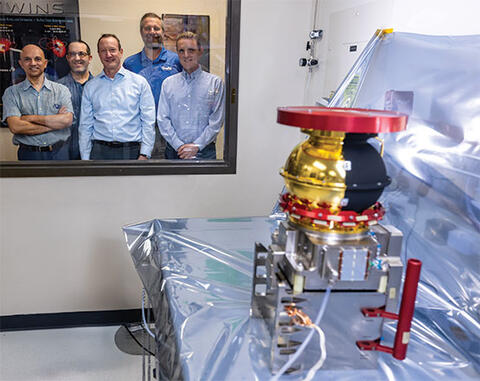

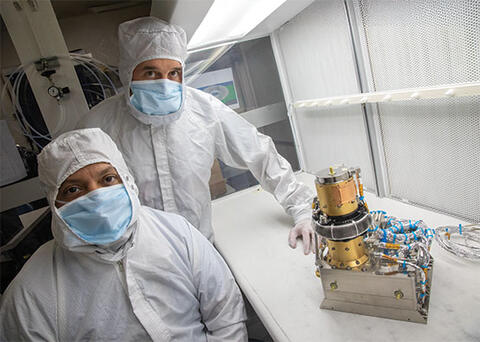

SwRI’s Jacob Friday (left) and Benjamin Rodriguez install red “remove before flight” protectors from the CoDICE instrument in preparation for delivery. The Sun-facing side of CoDICE is coated in a shiny ‘gold’ metal to reflect the heat of the Sun. The opposite side has a matte black surface designed to retain as much heat as possible to slow dissipation into the cold vacuum of space.

IMAP

The first satellite to deploy following launch was IMAP. SwRI played a major role in this mission, managing the payload office and providing a scientific instrument and other critical technology. SwRI Space Science Division Executive Director Susan Pope is the mission’s payload manager, Institute Scientist Dr. Mark Tapley is the payload systems engineer, and Group Leader Paul Bland is the payload safety and mission assurance lead.

SwRI’s CoDICE instrument team included, from left, Deputy Instrument Lead Dr. Mihir Desai, Flight Software Lead Greg Dunn, Quality Assurance Lead Tim Brenner, Project Manager Steve Persyn and Systems Engineer Jeremy Ford.

IMAP features the next generation of instruments that will provide improved data to meet mission objectives. SwRI managed the science and technology payload to achieve the mission’s goals through coordinated scientific measurements. IMAP will scan the heliosphere, analyze the composition of charged particles, and investigate how the particles move throughout the solar system. This will provide insights into how the Sun accelerates charged particles, helping to complete essential pieces of the puzzle needed to understand the space weather environment throughout the solar system.

After extensive bench testing, SwRI’s Dr. Frédéric Allegrini (left) and Ben Rodriguez install IMAP-Hi’s front-end-electronics board and IMAP-Hi’s detector for vacuum testing inside SwRI’s calibration chamber.

Image Courtesy NASA/UNH/Jeremy Gasowski

The University of New Hampshire’s Skylar Vogler (left) and SwRI’s Amanda Wester use UV light to detect and remove particles from the IMAP-Lo collimator grids and spacers.

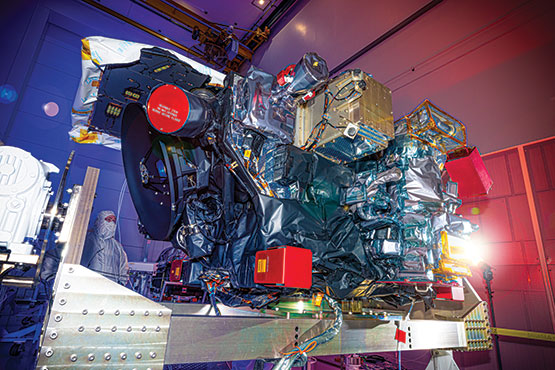

Image Courtesy BAE Space & Mission Systems

The SWFO-L1 satellite, shown during final preparations, is NOAA’s first satellite designed specifically for continuous, operational space weather observations. SwRI provided two of the four science instruments, SWiPS (silver and red instrument, top center) and SWFO-MAG, which will be deployed on an 18-foot boom.

IMAP will primarily investigate two of the most important overarching issues in heliophysics. Namely, how charged particles from the Sun are energized to form what’s known as the solar wind and how that wind interacts with interstellar space at the heliosphere’s boundary.

This boundary offers protection from most intense radiation originating outside our heliosphere — key to creating and maintaining a habitable solar system. The physics of the boundary and how it changes over time helps explain why our solar system can support life as we know it.

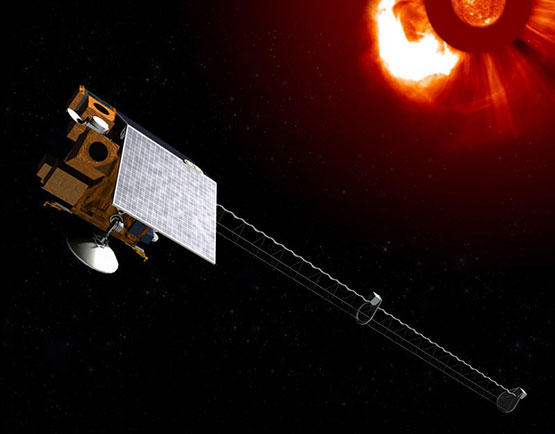

IMAP has been described as a modern-day celestial cartographer that will fill in blank spots on the map of the heliosphere. The spacecraft will study the Sun’s activity and how the heliosphere boundary interacts with the local galactic neighborhood beyond. A major focus for IMAP is to explore the space filled with plasma from the Sun that envelops all the planets in our solar system. Here, the outpouring of solar material collides with the local interstellar medium that fills the space surrounding the heliosphere. This interaction forms a critical barrier for high-energy cosmic rays at a distance of about 10 billion miles from the Sun.

IMAP will also examine the fundamental processes that accelerate particles throughout the heliosphere and beyond. The resulting energetic particles and cosmic rays can harm astronauts and space-based technologies.

DETAIL

IMAP is a follow-on mission to NASA’s Interstellar Boundary Explorer, which was led by former SwRI staff member Dr. David J. McComas. Now a Princeton University professor, McComas leads the IMAP mission, which has an international team of 27 affiliated institutions. The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, built the spacecraft and will operate the mission. IMAP is the fifth mission in NASA’s Solar Terrestrial Probes (STP) Program portfolio, managed by Goddard Space Flight Center.

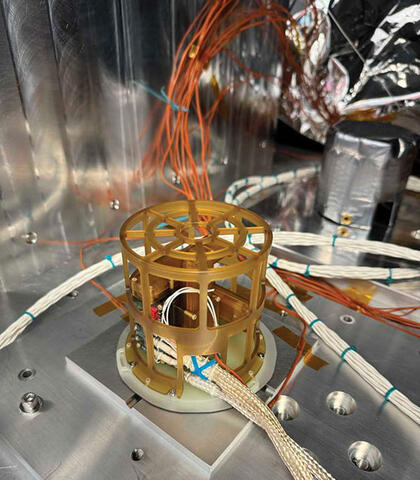

The Institute developed the novel CoDICE instrument, which combines the capabilities of multiple instruments into one patented sensor. Initially developed through SwRI internal funding, CoDICE will measure the distribution and composition of interstellar pickup ions, particles that make it through the “heliospheric” filter. Led by Dr. Stefano Livi with support from Dr. Mihir Desai and Dr. Keiichi Ogasawara, it will also characterize solar wind ions as well as the mass and composition of highly energized solar particles associated with flares and coronal mass ejections.

CoDICE combines an electrostatic analyzer (ESA) with a time-of-flight versus energy (TOF/E) subsystem to simultaneously measure the velocity, arrival direction, ionic charge state and mass of specific species of ions in the local interstellar medium (LISM) surrounding our solar system. CoDICE also has a path for higher energy particles to skip the ESA but still get measured by the common TOF/E system. These measurements are critical to characterizing the composition and flow properties of the LISM, determining the origin of the enigmatic suprathermal tails in the solar wind and advancing the understanding of the acceleration of particles in the heliosphere.

The SWFO-MAG instrument deploys two tri-axial fluxgate magnetometers on an 18-foot boom to measure variations in the interplanetary magnetic field carried by the solar wind.

CoDICE is about the size of a 5-gallon paint bucket, weighing about 22 pounds, and has a unique and beautiful thermal management design. The Sun-facing side of the instrument is coated in a shiny ‘gold’ metal to reflect the heat of the Sun. The opposite side has a matte black surface designed to retain as much heat as possible to slow dissipation into the cold vacuum of space.

SwRI built high-voltage power supplies for the Solar Wind Electron (SWE) instrument, which measures the distribution of thermal electrons in the solar wind, and the Global Solar Wind Structure (GLOWS) instrument, a non-imaging photometer that will observe the solar wind’s structure. SwRI also provided digital electronics for four other IMAP instruments.

SWFO-L1

The SwRI-built Solar Wind Plasma Sensor (SWiPS) and SWFO Magnetometer (SWFO-MAG) are two of four instruments integrated into SWFO-L1, NOAA’s first satellite designed specifically for continuous, operational space weather observations. From its unique vantage point at Lagrange Point 1 (L1), SWFO-L1 will monitor the Sun’s activity without interruption, providing quicker and more accurate space weather forecasts than ever before.

The SWiPS instrument, led by SwRI’s Dr. Robert Ebert, will measure the solar wind and detect solar transient events such as coronal mass ejections and interplanetary shocks that can cause adverse effects for Earth and its space environment. SwRI supports operations and data analysis for its onboard instruments. SWFO-L1 shared a ride to space with NASA’s IMAP mission before separating and traveling to the Earth’s L1 point, a point nearly one million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth.

SwRI’s Dr. Robert Ebert (right) and Prachet Mokashi led the development of the SWiPS instrument, one of two SwRI-developed instruments aboard NOAA’s SWFO-L1.

As part of SWFO-L1’s suite of space weather-observing instruments, SWiPS and SWFO-MAG will capture 24/7 observational data in real time to monitor abrupt changes in the solar wind often associated with coronal mass ejections and other space weather phenomena. When these phenomena interact with Earth’s magnetic field, they can have adverse effects on Earth and near-Earth technology. These effects can include electrical power grid disruptions, Global Positioning System navigation errors, spacecraft damage or potential harmful radiation exposure to astronauts. The SWFO-L1 data will support NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center and help predict and prepare for potential space weather impacts.

Image Courtesy BALL/NASA-SOHO

SwRI developed the SWFO-L1 MAG instrument, two sensors 13 feet (4 meters) and 18 feet (5.6 m) away from the spacecraft, mounted on a deployable boom. The instrument will monitor the Sun’s magnetic field for abrupt changes that are often precursors for geomagnetic storms that can interact with the interplanetary magnetic field and affect life on Earth.

SWiPS has two identical top-hat electrostatic-analyzer-based sensors, each capable of measuring the velocity, density and temperature of solar wind ions. The real-time, around-the-clock observations measure the plasma structures directed toward Earth, monitoring the solar wind for abrupt changes from interplanetary shocks, coronal mass ejections, corotating interaction regions, high-speed solar wind, etc.

DETAIL

Gravitational forces from the Sun and the Earth hold objects at Lagrange 1 (L1) in a stable position that offers an uninterrupted view of the Sun.

Geomagnetic storms can reconfigure Earth’s magnetosphere, the protective bubble surrounding Earth, which is disturbed by changes in the solar wind. SWiPS provides in-situ observations of the solar wind plasma directly upstream from Earth, providing an early warning of geomagnetic activity. SWiPS velocity measurements allow scientists to predict the arrival time of adverse space weather conditions. With this forewarning, public and private organizations affected by space weather can take actions to protect their assets.

Predicting the severity of geomagnetic storms is possible using measurements of the solar wind velocity, density, and temperature provided by SWiPS, along with information from the SWFO-MAG.

DETAIL

The SWFO-L1 mission is a partnership between NOAA and NASA. The NASA Goddard Space Flight Center managed the development of the SWFO-L1 observatory on NOAA’s behalf and to NOAA’s specifications. NOAA will operate SWFO-L1 from its Satellite Operations Facility in Suitland, Maryland, and process the space weather data at its Space Weather Prediction Center in Boulder, Colorado.

The SWFO-MAG instrument, led by SwRI’s Dr. Roy Torbert out of the University of New Hampshire (UNH) location, consists of two tri-axial fluxgate magnetometers that each measure the three components of the interplanetary magnetic field carried by the solar wind. The SWFO-MAG sensor’s elongated racetrack shape distinguishes it from the traditional circular ring-shaped magnetometers. The elongated design provides three benefits: it reduces noise by focusing the magnetic field along its length, has more definite orientation by aligning the magnetic axis with the mechanical axis, and enhances thermal stability by distributing heat more uniformly along each axis.

The two SWFO-MAG sensors are 13 feet (4 meters) and 18 feet (5.6 meters) away from the spacecraft, mounted on a deployable boom. The boom isolates the magnetometers from any spacecraft-generated fields, providing a quiet operational environment. By observing the solar wind, MAG provides real-time, around-the-clock observations of the magnetic structures directed toward Earth. The Space Research Institute of the Austrian Academy of Sciences provided SWFOMAG’s front-end electronics and its core electronics microchip.

SWFO-MAG is designed to provide NOAA and the scientific community at large with important data about the solar wind as it approaches Earth. The magnetic field variations are a key parameter in predicting the severity of a solar storm’s impacts on Earth’s magnetosphere. SWFO-MAG, which was built and tested in conjunction with UNH, will produce data to help mitigate space weather impacts.

Pathway Back to the Moon

IMAP and SWFO-L1 will join a fleet of NASA heliophysics missions that seek to understand how the Sun affects the space environment near Earth and across the solar system. In a very real way, these spacecraft and instrument packages are blazing the trail for further human exploration of the Moon and eventually Mars. We haven’t visited the Moon in over 50 years, and NASA is committed to making sure astronauts can safely explore our neighbors, with early warning systems in place to forecast potentially harmful space weather and galactic cosmic rays.

For more information, visit Heliophysics.